I had to change tactics.

I began to look at the company as an agile organism, tracking and monitoring the changes in the environment rigorously. Planning a year ahead? Half a year later, an unexpected regulatory change, or a sudden tactical move from a competitor, shattered our annual strategic plan. Detailed planning of projects? 2 weeks after plans were finalized, there came an unexpected twist from another project, from a freshly on-boarded senior stakeholder, or from a subcontractor. When 3-400 projects are running in parallel at the company, and the business environment is in constant motion, managing the outcome of a project becomes highly unpredictable and uncontrollable. Only key milestones and the end date provide something concrete to hold on to.

Not only business priorities and project plans fluctuated at an unpredictable pace, but so did people. There wasn’t any project over the 6 years I spent at Vodafone Hungary where personnel changes didn’t occur halfway through the project, loosing key people with their special, often irreplaceable knowledge and experience. As a program manager, my main responsibilities were to constantly detect risks, track changes, and to keep a cheerful mood in the constantly changing program team.

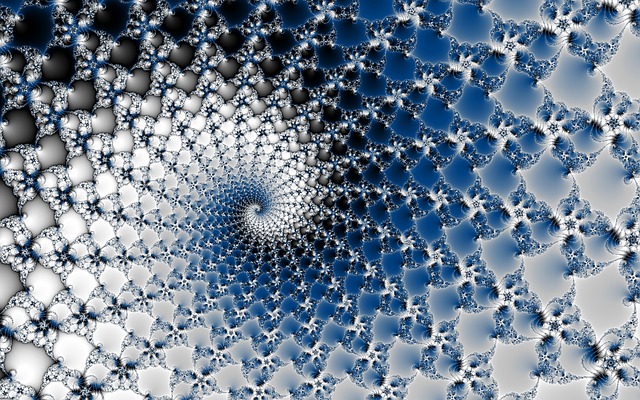

But still. The organization delivered results – even under these conditions. Consumers were able to make phone calls, use the Internet, we went to market with new products, and IT systems went live (albeit, with a lot of headache). I’ve tried to understand what’s behind this seemingly paradoxical way of functioning. Finally, I found some reassuring answer in chaos theory. Inside chaos, there is order, just like in the wonderful world of fractals. A project at Vodafone was a fractal of the organization, exhibiting patterns similar to the system as a whole.

What is the world of VUCA in which fractals are organized?

Similar to my experiences at Vodafone Hungary. The acronym VUCA, which stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous, was used by the American military in the late 1980s to describe the unpredictable, dynamically changing military situations of the post-Cold War era. However, the term has become widespread after the 2008-2009 economic crisis, to describe the challenges and complexities of strategic leadership, including the emergence of disruptive technology, big data, and the unpredictable business environment that make strategic planning and management impossible to handle.

According to scientific literature, there are many ways to combat the VUCA world. First, we need to provide strategic support to the leadership and management team so that they understand how each component of VUCA affects their business. Researchers at Kelly School of Business advises leaders to understand what each component of the VUCA acronym stands for and what are the business solutions to address them. They developed a framework to better manage the challenges encountered in VUCA.

It strikes me as a leadership coach that there is an increasing mental-psychological strain on leaders due to the uncertainty and unpredictability of the VUCA environment. Here, too, I can draw on my own experiences at Vodafone Hungary. During the years I noticed that there were times when I had to practice 2-3 hours of mindfulness and oriental concentration exercises daily before going to work to keep up with the stresses of the work. When I didn’t have my daily dose of practices I lost my efficicency halfway through the day. It also helped me develop my intuition to make good decisions in the rapidly changing project environment.

Apparently I wasn’t the only one struggling with this. One day, after a few years at the company, I asked another colleague, to tell me his secret of working there as a manager for 15 years. He said he would tell it to me only if I promise not to laugh at him. I waited with utmost curiosity what he wanted to say.

2 hours daily meditation in the morning – came the answer.

Order and Chaos

In ancient Chinese philosophy, chaos and order are two sides of the same coin whose fluidity is best expressed by the symbol of yin-yang. The black snake is chaos, with the core of order in white spot; the white snake is order, with the core of chaos in black. There is no order without chaos and no chaos without order – they are in constant flux with one another.

I experience it during my vipassana meditation retreats. The calmer the outside environment, the more turbulent my mind becomes. When we are not stimulated by the outside world, long-forgotten memories, feelings and thoughts emerge from the bottom of our mind. I am always perplexed to see how the silence of the outside world amplifies the noise of our inner world.

Understanding the above-mentioned yin-yang dynamics, I also realized while at Vodafone that if the environment in which we work is turbulent, with a constant flux of information and stimuli, the answer to survival is to calm our inner world. You need a calm and balanced mind to efficiently combat the outside world of stimuli and to scan the environment for information to make good decisions.

Perhaps Hungarian poet, Endre Mányoki, expresses it best in his poem, the Triple Road, how to understand the world of VUCA:

“Chaos is not a lack of order, but an order whose laws are still unknown to us.”